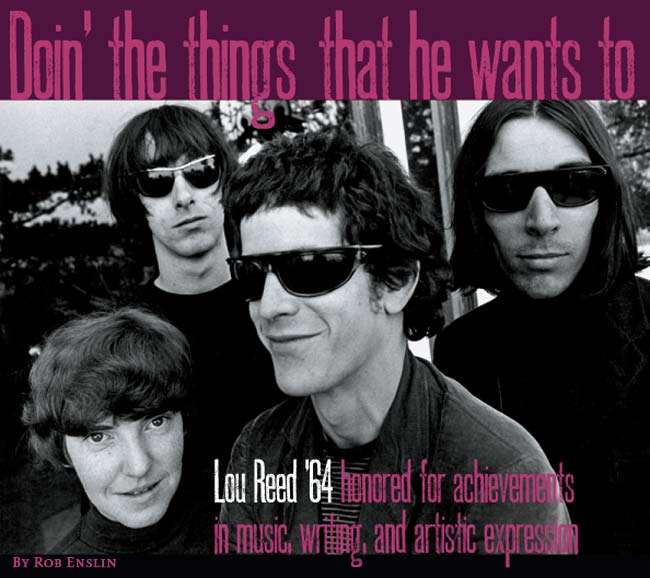

ou Reed is a funny guy. Really. Leave it to the Mad Monk of Rock to inject a little humor into his own Arents Award Celebration. Last April, at the way-beyond-hip W Hotel in New York’s Union Square, he opened his remarks with a peculiar anecdote. “You know, an interviewer asked me, ‘Is it true that police told you that you couldn’t attend graduation?” The audience chuckles nervously, especially those unaware of his student past at Syracuse University during the early ‘60s.

“I said, ‘Who would tell you such a thing? How could that possibly be true?’” And, taking a cue from Jack Benny, he deadpans, “Of course, it was.” The audience erupts. Reed is in control of the room. ou Reed is a funny guy. Really. Leave it to the Mad Monk of Rock to inject a little humor into his own Arents Award Celebration. Last April, at the way-beyond-hip W Hotel in New York’s Union Square, he opened his remarks with a peculiar anecdote. “You know, an interviewer asked me, ‘Is it true that police told you that you couldn’t attend graduation?” The audience chuckles nervously, especially those unaware of his student past at Syracuse University during the early ‘60s.

“I said, ‘Who would tell you such a thing? How could that possibly be true?’” And, taking a cue from Jack Benny, he deadpans, “Of course, it was.” The audience erupts. Reed is in control of the room.

I’m sitting only yards from Reed, sandwiched between two reporters at a dinner table that includes Britney Spears’ attorney, a VH1 executive, and Lou’s personal assistant. I try to get a read from the people at the table, especially the assistant, expecting some sort of shock or dismay, but I can see they’ve heard all this before. I haven’t touched my plate, nor will I, as the next few hours are spent digesting stories of a man who has been called everything from an art rocker to a white-noise merchant. To some, Lou Reed is the Phantom of Rock; to others, the Godfather of Punk, although he disdains that label. (“I’m too literate to be into punk rock,” he told an interviewer in 1977. “I don’t think I’m responsible for anything.”) What is certain is that Reed is brilliantly productive, a continuously evolving musician, writer, and photographer who manages to stay as edgy today as he was when he formed the Velvet Underground in 1965, just after graduating from Syracuse and moving back to New York City.

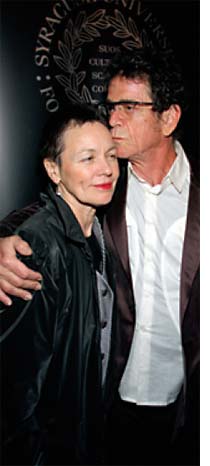

It takes a strong guy like Reed to make light of a colorful past. But on this occasion, he draws attention for a different reason: he is receiving the University’s most prestigious alumni award, the George Arents Pioneer Medal, and people are focused on his legacy. At the outset of his acceptance speech, he asks, “Who would’ve believed this one?” Reed is surely asking that question of everyone in the room—Bono, David Bowie, Laurie Anderson (his longtime partner), and a host other notables. But I have to agree with Camille Dodero’s assessment in The Village Voice that he is probably speaking to himself, as well. The prodigal son has come home.

“As a social psychologist, I can’t resist thinking a bit about why this community of Lou’s friends, fellow artists, and fellow alumni has come together tonight,” SU Chancellor Nancy Cantor tells the throng of well-wishers. She characterizes Reed as a “timeless poet” and “muse for us all,” praising his courage, compassion, and honesty. “Our mission is to instill the value of meaningful engagement to make things better…and to understand that it may take a ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ to do it,” she says, quoting his 1973 solo breakout hit.

If I told you I didn’t enjoy schmoozing with this crowd, I’d be posing. Mingling with top-shelf paparazzi and reporters from Variety and New York Magazine is admittedly cool. For some of the guests, the evening’s festivities are just standard fare. Look around: Marty Bandier ’62, chair and CEO of Sony/ATV Music Publishing; Ian Schrager ‘68, founding proprietor of Studio 54; and Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, a photographer and film director whose Grammy-winning biopic, Lou Reed: Rock and Roll Heart, is part of the evening’s activities. Entertainment mogul Rick Dobbis ’70, who emcees the event, doesn’t even flinch when Bono asks him to pass the butter. As for the rest of us, we can only imagine our responses, should David Bowie ask for salt.

|

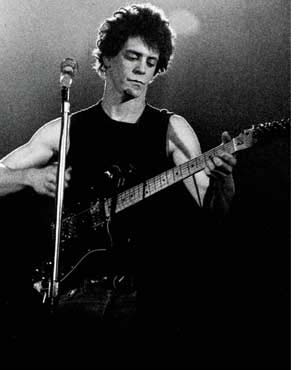

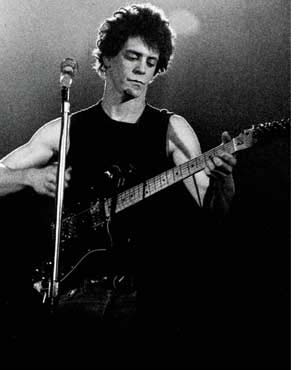

Reed in Copenhagen, 1975

LAU BUUR NIELSEN (COURTESY OF SAL MERCURI) |

But one thing binds us all—celebs and mortals—together. More than a hundred of us are here for Lou Reed. Amid frequent standing ovations and repeated chants of “Looouuuu,” the bespectacled honoree is feted again and again. SU English professor Mary Karr speaks of the University’s affection for “crazy outlaw poets,” such as Reed is, while novelist Oscar Hijuelos compares Reed’s artistry to the best writing of William S. Burroughs. “His range is potent,” Hijuelos tells me. “I mean, he has the kind of chops to find a subject for his art everywhere. His surreal expressionist photographs of New York have the same kind of dreamlike intensity as his finest songs.” With signature aplomb, Bono informs the audience that there is an alchemist in their midst. “Lou Reed not only inhabits his chosen universe, but he also creates it. Lou has turned the cosmic litter of this city into gold.” Following comparisons to James Joyce, the U2 front man closes with a wry dedication: “May your brain stay a squeaky wheel, and may your dirty boulevards never be squeaky clean.”

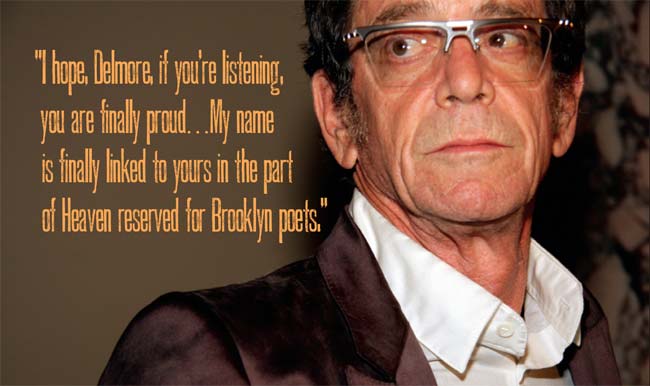

Not many rock stars graduate from college. Fewer still receive their alma mater’s highest honors. Perhaps just one establishes a major scholarship in memory of his professor. So it is a welcome surprise when Cathryn Newton, dean of SU’s College of Arts and Sciences, announces the Lou Reed/Delmore Schwartz Scholarship, benefiting an English major studying creative writing. “The student has become the teacher,” she says of Reed, who studied with the charismatic writer at Syracuse during the early ‘60s. “We take great pride in the continuation of the legacy passed down from Delmore to you, and now, to the next generation.” Reed manages to make the evening as much about Schwartz as himself.

|

Delmore Schwartz, Delmore Schwartz,

circa 1946

PHOTO COURTESY OF NEW DIRECTIONS PUBLISHING CORP. |

It’s a little known fact that Reed majored in English at SU, and less known still that he graduated with honors in 1964. But what is known is that prior to forming the Velvets, he studied with Schwartz, the poet and fiction master who died suddenly in 1966. Schwartz’s short story, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” was a shaping force in Reed’s simple, colloquial approach to language. Such classics as “Heroin” and “Waiting for the Man,” both penned by Reed while at SU, are prime examples. Some say Schwartz thoroughly infiltrated Reed’s creative sensibility, forging an aesthetic complement and counterweight to Andy Warhol, who later produced the Velvets. “I’m not surprised by his friendship with Lou,” says James Atlas, author of Delmore Schwartz: The Life of an American Poet. “Delmore was a powerful figure by that time and had friendships with a number of younger writers. Anybody with a serious interest in art and literature would have been someone Delmore responded to.”

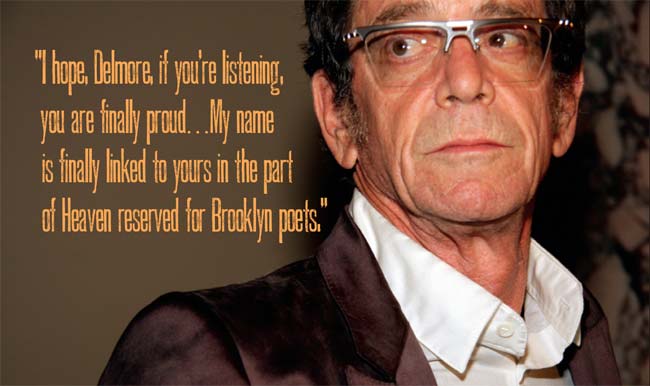

No one is more blown away than Reed, when Karr presents him with a rare autographed first-edition of In Dreams Begin Responsibilities (1938), the Schwartz collection in which the story that so deeply influenced Reed appears. “I will always love the University for giving me the opportunity to study from him,” responds the gravel-voiced New Yorker, casually clad in a rust-colored jacket, white button-down, and green slacks. “Delmore inspired me to write, and, to this day, I draw inspiration from his stories, poems, and essays. His titles, alone, were a writer’s dream.”

And still, there are encores. SU’s Belfer Audio Laboratory and Archive provides a recording of Schwartz reading his poem, “At a Solemn Musick.” Then Anderson renders heartfelt interpretations of two Schwartz poems, “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me” and “All of Us Turning Away for Solace.” “I hope, Delmore, if you’re listening, you are finally proud, as well,” says Reed, allowing a trace of emotion. “My name is finally linked to yours in the part of Heaven reserved for Brooklyn poets.”

|

Reed in New York, 2007

PHOTO © ERIC WEISS

|

agic and Loss—the title of Lou Reed’s evocative 1992 solo album—might be an adequate high-concept synopsis of his career. Born Lewis Allan Reed in 1942, the middle child in a middle-class Brooklyn neighborhood, he studied piano and music theory as a youth. His family eventually settled in the Long Island village of Freeport, where Reed played guitar in a variety of bands and wrote songs and poems that railed against authority, conformity, and suburbia. agic and Loss—the title of Lou Reed’s evocative 1992 solo album—might be an adequate high-concept synopsis of his career. Born Lewis Allan Reed in 1942, the middle child in a middle-class Brooklyn neighborhood, he studied piano and music theory as a youth. His family eventually settled in the Long Island village of Freeport, where Reed played guitar in a variety of bands and wrote songs and poems that railed against authority, conformity, and suburbia.

In Fall 1960, after two semesters at New York University’s former Bronx campus, Reed enrolled at Syracuse University. He threw himself fully into art, music, drama, religion, philosophy, and literature. At one point, he even studied opera. Reed soon made a name for himself on campus as host of “Excursions on a Wobbly Rail,” a “free jazz” radio show on WAER-FM, and as the founding editor of the short-lived literary magazine, Lonely Woman Quarterly.

Religion professor emeritus Gabriel Vahanian, best known for his pioneering work in the “death of God” movement, remembers Reed as a bright student with a competitive streak. “He had the capacity for entering into an argument,” recalls the 80-year-old theologian, speaking by phone from his home in Strasbourg, France. “Like everyone else in those days, Lou Reed wanted to rewrite religion, which he did with his songs.” Vahanian paints a compelling portrait of Reed as someone with a “chip on his shoulder,” but is quick to admit that he was a good student. “He had talent, there’s no question about it, in spite of all the differences between him and the other students,” Vahanian recalls. “But most of my students hated each other.”

|

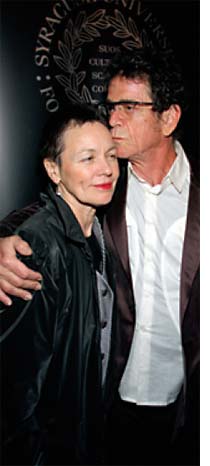

Laurie Anderson and Reed at the Arents celebration in New York City.

PHOTO © ERIC WEISS |

Whereas Vahanian hoped Reed would pursue a career in religious studies, Delmore Schwartz found the makings of a serious writer in Reed. Schwartz held court with his star student at the far back corner table of the Orange Bar, a legendary space on Crouse Avenue, inches from campus. Today it is nothing more than a surfer bar without an ocean, but back in the day, it was where Schwartz—the “Mozart of conversation,” as Saul Bellow called him—regaled students with ribald tales about James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, and Queen Elizabeth II. Tragically, the comfortable dive only served to exacerbate Schwartz’s addiction to drink and speed, but not before instilling in Reed an abiding interest in poetry. “Lou Reed is as much a poet as he is a performer, and really sees himself that way, in the Bardic tradition,” says James Atlas. “I think

he appreciated and responded to the obvious tragedy that was going on in Delmore’s life.”

“Had Lou Reed gone to another school, we probably wouldn’t be talking about him right now,” speculates Joe Harvard, author of The Velvet Underground and Nico. “The specific atmosphere at Syracuse, vis-à-vis certain teachers and things he was exposed to, created the Lou we know. His ability to see the syntactical relationship between any art form and another—music, literature, and film—is why some of the great Lou Reed and Velvet Underground songs are cinematic. They have the quality of a vignette that’s beautiful and poetic.”

At SU, Reed found time to play in a variety of bands, including the Eldorados, who became the darlings of the local bar-and-frat circuit. Out of that experience grew friendships with guitarist Sterling Morrison and James Tucker, whose younger sister, Maureen (“Moe”), played drums. After graduating and spending a year as a songwriter at Pickwick Records in New York, Reed reunited with Sterling and Moe to form what would eventually become the Velvet Underground. Rounded out by John Cale, a classically trained violist Reed met at a party, the group played its first gig at Summit High School in New Jersey in December, 1965. Dark and subversive, with a flair for the avant-garde, the band was sacked early into what was supposed to be a two-week gig at the Café Bizarre in Greenwich Village—but not before catching the attention of Andy Warhol. Looking for a sonic outlet for his ideas and visual imagery, the artist promptly signed the Velvets to a management deal, uniting them with the German chanteuse Nico.

The relationship with Warhol was short-lived, but not without advantages. The artist bathed the band with equipment and rehearsal space, not to mention entrée into New York’s hippest, most flamboyant circles. The Velvets advanced their outlaw reputation as part of Warhol’s live multimedia show, The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, a potent combination of live music and raw performance art. Perhaps no one was more optimistic than Reed when the Velvets were taken to New York’s Scepter Studios in April, 1966, to record an album. The Velvet Underground and Nico would take a full year to release, and it would fail miserably on the charts, ultimately costing the band its manager and female singer. But the album—now celebrating its 40th anniversary—would ensure the Velvet Underground its place in rock history.

“The reason the album sounds ‘immediate’ is because they did it on my money, and I didn’t have much of it,” admits Norman Dolph, who put up $800 for the band’s four days at the venerable R&B studio. An art-collector friend of Warhol’s who happened to be a Columbia Records executive, Dolph booked the band studio time during the day, when it was supposed to be under renovation, an arrangement that allowed the band to continue gigging at night. “The people who worked at Scepter saw this going on and thought it was weird because you had a white rock group making an album at a place chiefly known for Dionne Warwick and the Shirelles,” he recalls.

Dolph, who is erroneously credited as the album’s co-engineer, remembers the band members as deferential to Nico and Warhol, the latter of whom showed up in the control room for only about a quarter of the sessions. “Warhol, as a person, probably said fewer words per minute than any guy I met. You’d say something, and he might comment on it. He didn’t try to be droll or weird.” What stands out in Dolph’s mind were Reed’s get-it-done attitude and his desire to recreate the live show in the studio. “’Heroin’ was an incredible thing when he did it,” Dolph says. “It was not dizzy or out of control or as you might expect it to be if sung by an addict. It was delivered as an actor, familiar with the role, might portray it. It was a very emotional delivery.” Rolling Stone contributing editor Anthony DeCurtis praises the song’s lyrics. “That part in ‘Heroin’ about a ‘Great big clipper ship/Going from this land here to that’ is brilliant,” he says. “At his best, there’s nothing inessential in a Lou Reed lyric.”

To say The Velvet Underground and Nico is influential is to flirt with the obvious. Rolling Stone named it one of the “40 Essential Albums of 1967,” praising it for its “urban decadent subject matter and bummer vibe,” and singling out “Heroin” as one of “40 Songs That Changed the World.” (In 2007, the album’s original acetate, which inadvertently sold at a garage sale for 75 cents, fetched $40,000 on eBay.) Both the music and artwork—especially Warhol’s stark, phallic banana—are about as far removed from the “Summer of Love” as imaginable. Yet, like the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s, they point toward new styles of thinking. “The rawness has a lot to do with it,” says Moe Tucker, now living in Georgia and all but retired from music. “I don’t want to say it’s unrehearsed; it just sounds live. Lou would bring in a song, and we’d fool around with it till we were happy. It wasn’t a conscious decision to sound lean.”

When the album stalled on the charts, the Velvets parted ways with Warhol and Nico. The band went on to record White Light/White Heat (1968), Loaded (1969), and The Velvet Underground (1970), all too controversial for mainstream audiences, but enduring, influential classics, nonetheless. Meanwhile, Cale was replaced by Doug Yule in 1968. Reed dissolved the group two years later, embarking on a solo career that has since yielded nearly 30 albums, reflecting a life’s work of remarkable breadth, depth, and maturity. “The nature of his lyric writing had been hitherto unknown in rock,” writes David Bowie, who co-produced Transformer, Reed’s seminal 1972 album, which helped usher in glam rock. “He supplied us with the street and the landscape, and we peopled it.”

“His songs, for all their ferocious simplicity, have been a real cornerstone for people learning how to play guitar,” observes Rolling Stone senior editor David Fricke, who has covered Reed for more than two decades. “That’s one of the great lessons of Lou and the early Velvets material. If you take those rock ‘n’ roll basics and have a story to tell, then you’re off to the races.” Nobody knows this better than singer Fred Schneider and guitarist Keith Strickland, both of The B-52’s, which spawned the now-legendary alt-scene in Athens, Georgia. “Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground had a big influence on us, as they did on every punk and new wave band,” remarks Schneider. “Their experimenting with sounds and lyrics, the chances taken, the attitude and sense of danger, along with a sense of humor, all made for an original music that holds up strong to this day and probably forever.” Strickland concurs. “They introduced us to a whole new realm of possibilities as to what a rock and roll band could be—what you could write about and the way you could play your instruments. It was very liberating and made me feel that I could do it.”

Ever the nonconformist, Reed has been enshrined as part of rock’s establishment. He has been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, along with the Velvets; conferred as a Chevalier (Knight) in the Order of Arts and Letters by the French Government; and named recipient of the prestigious Hero Award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. He has even performed for the Pope. You might say Reed has established a good place for himself. “Lou is a strong-willed person of great depth and creativity, who is able to survive events that might have crippled lesser men. All this has gone into the formation of Lou’s style,” explains Doug Yule. “The biggest misconception about him, as a person, is that anything that has been written or spoken about him bears little relation to whom he really is.” Velvet Underground aficionado Sal Mercuri adds, “There’s a touch of empathy to everything Lou does. He treats his subjects with respect. How many people can write the way he does—not only songwriters, but also plain, old writers? Lou found his style early on and has managed to remain true to it.”

efore his death, Delmore Schwartz warned Lou Reed that if he ever sold out or wrote junk, he would come back to haunt him. Knowing this, I could not resist an opportunity to see rock’s famous iconoclast in action a few nights after the Arents event, at the HighLine Ballroom in Chelsea. Reed is the inaugural headliner for this slick, two-story venue, opening during David Bowie’s new HighLine Festival. It is also part of a larger effort to revitalize the lower West Side by reclaiming the “High Line,” a long-moribund elevated freight railway. I fall by the W Hotel for directions and spend the next hour making a crosstown pilgrimage west from Union Square to the meat-packing district, retracing steps Reed made some 40 years ago as a member of the Velvet Underground. I mutter to myself when I notice that Max’s Kansas City, just blocks from the swanky W, is now a deli. I pass another Reed landmark on the way: the Chelsea Hotel. It endures. efore his death, Delmore Schwartz warned Lou Reed that if he ever sold out or wrote junk, he would come back to haunt him. Knowing this, I could not resist an opportunity to see rock’s famous iconoclast in action a few nights after the Arents event, at the HighLine Ballroom in Chelsea. Reed is the inaugural headliner for this slick, two-story venue, opening during David Bowie’s new HighLine Festival. It is also part of a larger effort to revitalize the lower West Side by reclaiming the “High Line,” a long-moribund elevated freight railway. I fall by the W Hotel for directions and spend the next hour making a crosstown pilgrimage west from Union Square to the meat-packing district, retracing steps Reed made some 40 years ago as a member of the Velvet Underground. I mutter to myself when I notice that Max’s Kansas City, just blocks from the swanky W, is now a deli. I pass another Reed landmark on the way: the Chelsea Hotel. It endures.

By the time I arrive at the HighLine, it’s 9:30 p.m.—early by New York City standards. The place is already filling up with rabid fans, industry insiders, and aging hipsters. In Reed’s downstairs VIP area, I spot Paul Shaffer, bandleader on The David Letterman Show; Richard Belzer, who plays Munch on Law and Order: S.V.U.; Reed’s bulletproof manager, Tom Sarig; and his long-time Tai Chi instructor, Master Ren. Punk-folkies Okkervil River make a brave attempt to incite the crowd, until the Phantom, himself, appears, looking remarkably buff in a dark tank top and baggy jeans. Behind him are faces familiar to most Reed fans: guitarists Mike Rathke and Steve Hunter, bassist Rob Wasserman, and cellist Jane Scarpantoni. No need for a drummer with a lineup this good.

Again, Reed assumes control. At the beginning of the second song, “What’s Good,” he snaps at the sound guy for not paying attention and then orders the smoke machine to be cut. “I don’t want to find out 15 years from today that you quit smoking, but that you used that smoke machine,” he warns. With the technical kinks worked out, Reed settles into the music, with satisfying results. Anyone expecting Velvet Underground classics, like “Venus in Furs” or “Sweet Jane,” or the perennial Reed chestnut, “Walk on the Wild Side,” is sorely disappointed. Instead, he serves up sparse arrangements of later, less well-known solo material, bracketed by “Dorita” and the title track from Magic and Loss. Included are diary recitations from Songs for Drella, a 1990 tribute to the late Warhol; a hypnotic version of “Ecstasy”; updated renditions of “Trade In” and “Sword of Damocles”; and surprise appearances by saxophonist John Zorn on “Magic and Loss,” and “Rock Minuet,” the encore.

|

Greg Kalamar’s rendering of the HighLine Ballroom show in New York City.

© GREG KALAMAR |

I stand next to Greg Kalamar, a well-known artist from California who is working on a sketchpad. He is poised between stage right, where we can virtually reach out and pluck Scarpantoni’s cello, and the gated VIP area. We compare notes all evening on everything from Reed’s distorted guitar playing to the two deliriously drunk girls next to us. (We almost lose it when the barkeep scolds one of them for lighting up!) As we swap cards, Kalamar promises to send me a finished version of one of his illustrations. Nice.

“It was very different from a typical Lou Reed show,” Anthony DeCurtis comments a few weeks later. “For one thing, it’s more typical to see him in a theater or a larger place, so it was very visceral. The stuff with John Zorn was extraordinary.” DeCurtis describes the evening as a tour through the byways of the Reed catalog, calling the songs well-chosen and powerful. “Talk about ‘Doin’ the Things That We Want To,’” he quips, referencing a lyric from 1984’s New Sensation.” It was inspiring.” Says Sal Mercuri: “Lou is at his best when he does it his way. When this kind of show happens, I’m glad I’m there. You get to see the man work the way he wants.”

The scene backstage, after the show, is almost as frenetic as the concert. Close friends, including Antony, the single-named leader of Antony and the Johnsons, a New York band, pays his respects to Reed, who is uncharacteristically giddy. “We were hot tonight,” beams the singer, wineglass in hand. “The band was magnificent, weren’t they? It was a good room.” I yak it up with several of Reed’s musicians and members of Okkervil River, who do not hide their awe at being in the presence of the Great One. Reed staggers over and, between puffs of a cigar, admits to the Austin indies that he discovered them online. “I needed an opener, and I legally downloaded you from the Internet,” he tells them, consciously provoking their incredulity. “I paid money to download your songs!” It’s not clear who is more impressed by the confession—Reed or Okkervil River. The young band is nonetheless honored.

After a quick detour with Paul Shaffer and John Zorn, who pepper their comments about Reed with superlatives (“genius,” “avant-garde”), I return to the inner sanctum, where Reed holds forth with Laurie

Anderson, Master Ren, and several Tai Chi buds. Anderson listens intently, as conversation takes an inevitable plunge into the finer points of the ancient martial art, which Reed began studying in the ’80s, and now practices up to four hours daily. The performer pulls me forward and proudly reveals a cut on his ring finger, inflicted by Master Ren during a recent training exercise. Neat. He then talks about Chen, a style of Tai Chi incorporating deep stances, twists and turns, and explosive power moves that helped him regain balance earlier that evening when he lost his footing onstage. I tell him I hardly noticed. “That’s Tai Chi for ya,’” he marvels. “It’s all about control.”

“I can’t think of many musicians who get up and do what Lou does and are in the shape that he’s in,” Timothy Greenfield-Sanders confides a few days later. “I don’t think he does Tai Chi because it’s gonna’ make him a better musician. He does it because he wants to feel good, have energy, and do all the things he wants to do at age 65.”

Perhaps it is this discipline—offset by a dry, caustic wit—that has allowed Reed to remain vital without taking himself too seriously. In a recent interview, he was reminded about once claiming to be too smart to be the Godfather of Punk. “I said that? No. No way…That’s crazy. C’mon, look at what I write,” he jokes. His walk on the wild side is far from over. |